No place like home

With opportunities to live and work all over the country and the globe, the resources sector is a drawcard for those seeking adventure. But, once their thirst is sated, most can’t wait to come back to South Australia...

SAM FRANCOU

GENERAL MANAGER SURFACE, OLYMPIC DAM, BHP

From Moomba to the Pilbara, Leigh Creek to the Bowen Basin, Singapore to South Australia, Sam Francou’s almost three decades of working in the resources industry have taken him to some of the world’s most unique remote landscapes – but his home state has always lain closest to his heart.

Francou began his career working FIFO in the Cooper Basin, located near the borders of northeast South Australia and southwest Queensland.

His varied role covering pipeline, surveying and engineering work giving him a broad experience of the sector and a strong basis on which to expand his career: working his way from production superintendent and metallurgical manager for Anglo American in Queensland to now general manager surface execution for BHP at Olympic Dam. Along the way he has worked as a production manager, organisational design program manager, senior manager production, and underground production and development manager.

It’s an impressive resume and one Francou credits to the opportunities for career advancement the resources industry offers. “To begin with, I changed jobs because there was an opportunity to get a different role somewhere else and to move around a bit,” he says. “Since I’ve been at Olympic Dam, I’ve gone into various roles because it gives me a good opportunity to ply the skills I have developed in the various roles I have held over the years into different areas.”

After years spent living interstate and internationally, Francou and his family finally returned home in 2015. “Both my wife and I are both from Adelaide so I must admit the opportunity to come back to South Australia was really appealing,” he says.

“We have family here, which is important for us; and a lot of friends. It’s also just a very good spot to live. Adelaide is the sort of city where you can get yourself really well set up. Our girls go to the nearby school and my wife is a teacher in town. My youngest daughter is currently in Year 8 and the aim is to remain in South Australia at least until she gets through Year 12.”

Francou has been in his current role – which involves looking after the concentrate area, the smelter and the refinery – for just two short months but has no concerns about taking on a new job while many are losing theirs due to the fallout from COVID-19. “BHP has been a fantastic employer, particularly through this period,” he says. “I’m grateful to have the opportunity to work at Olympic Dam and I think a lot of people are grateful for the way the resources industry has managed through the really tough times.”

JESSICA BALASSO

HEAD OF TECHNOLOGY, OLYMPIC DAM, BHP

A country girl at heart, it is little surprise Jessica Balasso began her career in the resources industry working in regional parts of Australia. Growing up on a farm in the Clare Valley, Jess adapted easily to living in the remote Roxby Downs community when her husband found work as a forklift driver at Olympic Dam in 2007. With a background in retail management, Balasso soon found work in a recruitment role for a labour hire company.

Initially the couple’s plan was to spend two or three years at Olympic Dam to save enough money to return to Adelaide to buy a house.

But, like all best-laid plans, theirs hit a bit of a fork in the road and it wasn’t until October last year that the couple finally made their way home.

Those intervening years saw Balasso move from recruitment to resources and the couple move from Roxby Downs to Whyalla and Port Hedland where, in 2011, she was offered a role with BHP Billiton as superintendent in the rail production division, responsible for managing a team of 270 people, including train drivers transporting one of the company’s most precious commodities.

“Iron ore is a huge part of BHP’s profit so there was quite a lot of pressure,” Balasso recalls. Her success led her to take on her next role: superintendent locomotive maintenance. When BHP Billiton rebranded to BHP in 2017, Balasso took on a new role leading the Port engineering team at Port Hedland; since then she has managed an improvement program and now runs a technology team that covers everything from basic IT issues to looking after mining communications and control systems. It’s this latest role – one she actively sought out – that brought Balasso and her husband back to Adelaide.

“Last year, both of our parents had a couple of health concerns,” she says. “And we have 12 nieces and nephews in South Australia who are growing up, so we started thinking 10 years in WA is probably long enough away – if we don’t get home and spend some time with family, we’re going to miss the boat.”

While mainly office-based, Balasso’s role does require frequent on-site visits, giving her the chance to return to where it all began. “It felt a bit weird to walk back into Olympic Dam in a totally different job – lots of things are the same and lots aren’t: but it’s been great,” she says.”

Now firmly ensconced back in Adelaide, Balasso has put her travelling days behind her … probably. “I’m very settled and happy and excited about the team I work with,” she says. “But the great thing about the resources industry is you can work through so many different types of jobs, and you can move around the world or stay in one spot. There are just so many options.”

Golden key to cancer cure

It’s not just pretty to look at – gold is proving to have invaluable properties in the fight against one of the world’s biggest killers

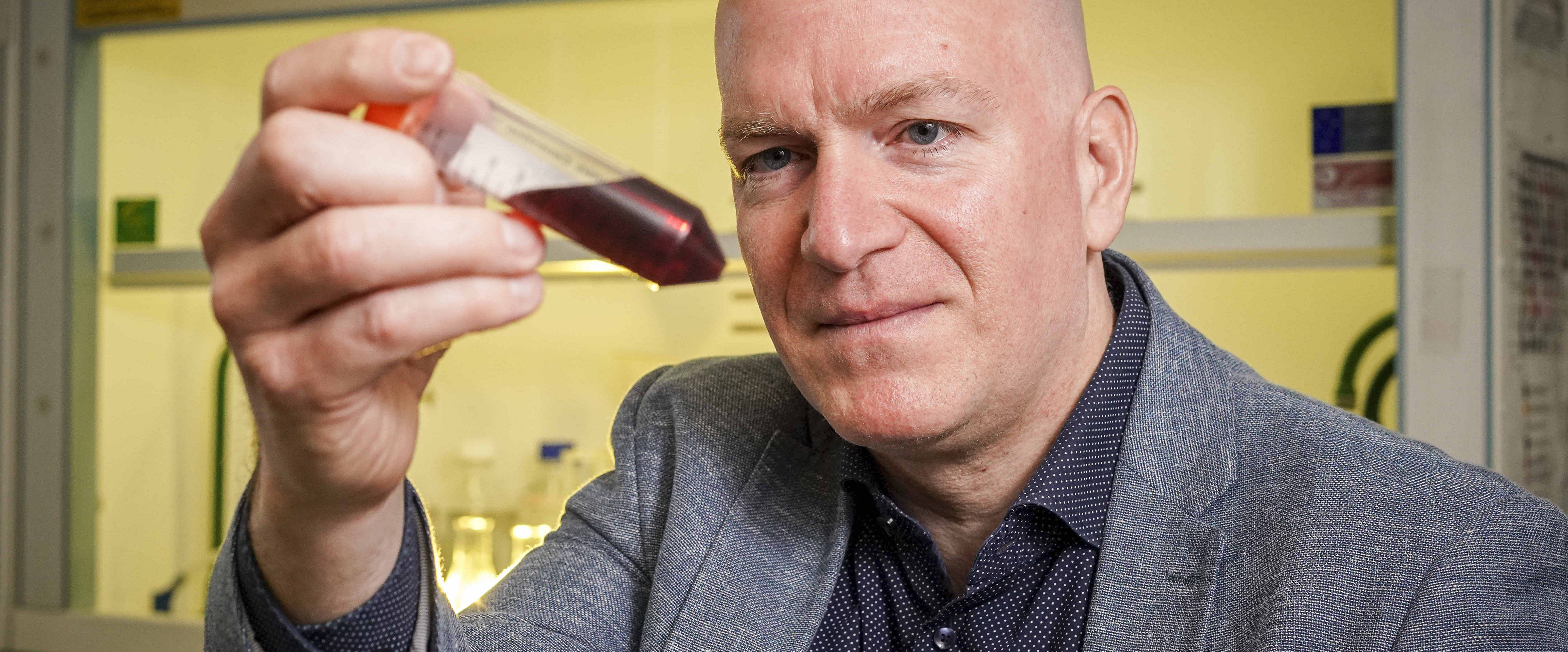

There’s always been something magic about gold. Its colour. Its shine. Its resilience. Now it’s proving to have some unexpectedly powerful medical properties. “Your body doesn’t like strange things inserted in it and will fight them. And it’s very efficient at doing that,” says Flinders University physical chemist Dr Ingo Koeper. And that’s where gold shines.

It’s inert. It doesn’t do much when mixed with most other things, which is the same lack of reactivity that has made it so popular among jewellers for tens of thousands of years. “Gold is very nice because the body doesn’t do anything with it. It doesn’t trigger an immune response,” he says. “Once the body detects the gold, it simply bundles it up in proteins that designate it as ‘waste’ to be excreted.”

And, just as gold can be easily shaped into exotic forms by artists, it is also particularly useful in a chemist’s hands. It’s becoming a significant force in the rapidly unfolding world of nanotechnology. “Gold has a very interesting chemistry that makes it very easy to design these nanomedicines or nanoparticles to manipulate their surface chemistry, so it enables that preferential targeting of cancer cells,” says UniSA biophysicist Dr Ivan Kempson.

This applies to radiotherapy, where healthy cells can become unwanted “collateral damage”.

“Radiotherapy is used in about 50 to 60 per cent of cancers,” Dr Kempson says. “For some, there’s very good therapeutic outcomes. In other cases, there’s a real need to try to enhance it.”

Which is where nanotechnology comes in. Cancers produce unique molecule “keys”. Matching receptors can be attached to gold, allowing it to latch-on to cancerous cells. “If we are enhancing the treatment where we want it to be, it means we should have better effect without causing more damage to healthy tissues,” Dr Kempson says.

Once attached, the gold can be bombarded with infra-red light or X-rays to heat-up and destroy cancer “and leave the healthy cells to be healthy and continue doing their thing”.

Nanotechnology is a relatively new science. So starting with an inherently safe material such as gold makes sense. But gold has much more to offer

Dr Koeper’s team was researching the ability of nano-gold to carry antibiotics deep into wounds when they discovered another unexpected benefit. “It seems it improves how efficient the antibiotic is,” he says.

When paired with gold nanoparticles, an antibiotic’s performance can be some 50 per cent greater than usual. Problem is, he’s not exactly sure why. Yet.

“We think that something is happening at the molecular level. Perhaps they can interact with the bacterial cell membranes in a way the antibiotic can exploit. It’s behaving like a catalyst.”

He hopes that figuring this out will unlock a whole new field of targeted medicine. “What do nanoparticles do to cell membranes? We need solid data and understanding before we can take this further.”

Dr Koeper’s team hopes to eventually produce a nano-gold slow-release antibiotic coating for implants, such as artificial hips and metal pins. As well as long-lasting antibiotics for surgical wounds.

“We are really trying to understand what’s happening,” he says. “Why is this more efficient? Once we understand this, we can transfer that knowledge to other applications.”

But what makes gold nanoparticles fundamentally useful, he says, is that they are an “all-terrain” vehicle. And it’s a vehicle to which tailored “tools” can be attached. “You can put whatever you want on it,” Dr Koeper says. “You can change the functionality of the particles to suit your needs. Or you can change how it looks from the outside – say, to bacteria. You can make it soluble or insoluble in water. The same with fats. So, for chemists, that’s quite useful.”

And that’s where the promise of nanomedicine lies. “You can program its ‘GPS’ system so it knows where to go. But the gold itself won’t damage the terrain through which it must pass,” he says.

Gold’s medical properties are now being enthusiastically explored across the world. It’s not just because it’s so flexible. It’s because it’s so stable.

“Making gold nanoparticles is really easy,” Dr Koeper says. “It’s a one-pot chemistry. You mix things. You wait. You have nanoparticles.

“You can do the same with silver nanoparticles but they’re not as stable. They fall apart much easier than gold. You can also use polymer nanoparticles, but they’re more difficult to make.”

GOLD

Gold doesn’t like to react with its environment.Which is why its yellow gleam stays constant over the centuries.

But it’s very soft, which is where the carat measure comes in. At 24 carats, gold is pure.

But it's too soft to be very useful. Which is why 18 carat gold alloys are more common.

Gold also conducts. This is why it’s often used to coat other metals such as copper: it prevents them from corroding.

Its lack of reactivity also puts gold at the heart of some computer chips where resilience is vital.